The Lost Art of Katrina

The Lost Art of Katrina

The Lost Art of Katrina

Originally published in 2006 in Lost magazine.

“As paintings go, it was not that good, really,” Madeleine McMullan recalls in a voice still gilded by pre-war Austria after 60 years in the United States. “I don’t even know who painted it. It wasn’t considered valuable — in fact, my father hated it.” McMullan is talking about a portrait of her mother that was painted in Vienna in 1920, smuggled out of the country when the family fled the Nazis on the eve of World War II, and lost on the surge of Hurricane Katrina last year.

The last time McMullan saw the portrait, it was hanging above her prized Louis XVI settee in the hallway of her family’s summer home in Pass Christian, Mississippi. It was a centerpiece of the house, which was built in 1845 with tall windows and broad galleries to catch the breezes and a sweeping view of the Gulf of Mexico. The moment she hung it there, in an alcove, McMullan knew she had found the perfect spot. Or so it seemed.

Done in oils in a style known as decote , the portrait was among precious few mementos of her family’s peripatetic saga, which unfolded across four turbulent years as Europe disintegrated, and culminated in their arrival in Baltimore in 1940. On a bright autumn day in Lake Forest, Illinois, where McMullan and her husband Jim live for most of the year, she recalls her family shuttering their three-story manse on Vienna’s Hofzeile Strasse, preparing to flee. It was a defining moment in her own history of loss and survival.

As they were preparing to leave, everyone knew the importance of concealing valuables from the Nazis, she says. Already her grandmother had taken the family silver to Geneva on repeated train trips, hidden in her handbag a few pieces at a time. Someone — McMullan doesn’t remember who — removed the portrait from its frame and folded it before the family fled, first to Switzerland, next to France, then to England, and finally to the U.S. The grand old house in Vienna, with all their remaining possessions, including a large collection of art, was bombed to rubble during the war.

McMullan inherited the portrait, which still bore the crease marks from the folding, after her father’s death, and she took it to the summer home in Pass Christian. After trying it in several rooms, “I finally found that perfect spot in the alcove, and there I put my mother,” she says.

Though the house was among a handful to survive Katrina along Pass Christian’s East Scenic Drive, it was gutted by 145-mph winds and a 30-foot tidal surge, which carried away two-thirds of its contents, ripped out some floors, exploded walls, and battered the arching live oaks on the lawn. With so much loss all around, with bodies being pulled from the wreckage up and down the war zone that the Gulf Coast had become, and with neighboring New Orleans descending into chaos, McMullan realized that her family was comparatively fortunate. Her mother’s portrait was a footnote to the worst natural disaster, the worst historic preservation disaster, and — as is only now becoming apparent — arguably the worst single loss of cultural artifacts and art in U.S. history. In New Orleans there was unimaginable ruin; in Pass Christian and elsewhere along the Gulf Coast, there was obliteration. Still, her mother’s portrait was something that had seemed destined to survive, and now it was gone and no one knew where it went.

Across Mississippi’s coastal counties, more than 65,000 homes were destroyed by the storm, and on the beach facing the Mississippi Sound, a residential esplanade running intermittently for perhaps 50 miles was reduced to flotsam and jetsam in a matter of hours, the wreckage interrupted here and there by the husks of the few ravaged structures that survived. Amid the bewildering enumeration of lost lives, it took a while for most people to recognize what else was gone: The feeling of permanence that had set the Mississippi Coast apart from typical beachfront communities of stilted houses and fake stucco condos. Hundreds of historic buildings were destroyed — buildings that had survived countless hurricanes, some for as long as two centuries — and many, including the McMullans’ house, discharged upon the wind and surge extensive collections of art. Countless collections, such as one that vanished from a home across the bay, which reputedly included works by Rembrandt and Picasso, were irreplaceable. Because the Gulf Coast was also a mecca for artists, the loss of such private collections was exacerbated by the destruction of artists’ studios, museums, galleries, and public buildings in which local art was on display. “We’ve lost art on a grand scale,” is how Biloxi attorney and art collector Patrick Bergin describes the cataclysm. Bergin, who rode out the storm with his family in their home on the Back Bay of Biloxi, recalls frantically moving as much of his art as possible upstairs as the rising water swept through the ground floor, but says much of the collection was lost anyway. “And it’s heartbreaking,” he says, “to think of everything in those 100-plus-year-old houses on the beach — all the antiques, heirlooms, art, sculpture — washed out into the Gulf or buried under debris.”

Even as the losses are being reckoned, random pieces of art have been found among the sodden drifts of clothing, building timbers, broken china cabinets, blinded TV sets, and rank refrigerators. In one odd coincidence, an Ocean Springs, Mississippi, woman found a water-damaged watercolor, of a marsh scene, in a marsh. Such finds have provided a source of both inspiration and bewilderment, leaving artists and collectors to wonder: Where, exactly, did it all go? For many, including Long Beach, Mississippi, collector David Lord, this is anything but an idle exercise. Lord lost a personal art collection whose value he estimates at more than $7 million, and he has no idea where it went or whether he will see any of the pieces again.

Even as the losses are being reckoned, random pieces of art have been found among the sodden drifts of clothing, building timbers, broken china cabinets, blinded TV sets, and rank refrigerators. In one odd coincidence, an Ocean Springs, Mississippi, woman found a water-damaged watercolor, of a marsh scene, in a marsh. Such finds have provided a source of both inspiration and bewilderment, leaving artists and collectors to wonder: Where, exactly, did it all go? For many, including Long Beach, Mississippi, collector David Lord, this is anything but an idle exercise. Lord lost a personal art collection whose value he estimates at more than $7 million, and he has no idea where it went or whether he will see any of the pieces again.

Today, a year after the storm, as the Gulf Coast echoes with the din of backhoes and dump trucks hauling away the last of an estimated 40 million cubic yards of debris, “gone” is not a satisfactory — nor, in many cases, an accurate — explanation, which makes it hard for collectors and artists to find closure or to envision what the future might, or should, hold. With so many places to search, with so much inscrutable evidence constantly assaulting the eye, “I do lie awake at night wondering,” McMullan says. Might her mother’s portrait one day be recovered, or, barring that, might she learn how it met its end?

The possibilities, of course, are endless. McMullan’s portrait might lie buried in the muck and sand of the offshore waters, or it could be hanging in a treetop with the drapery and clothes that flutter like tattered prayer flags across the coast. It could have washed up on a beach in Texas, or Yucatan, or it could be buried with all the other unseen treasures in the scores of landfills that were hastily permitted in inland counties after the storm. It could, conceivably, eventually show up on eBay. The storm surge of Katrina was the largest ever recorded in North America and swept as far as ten miles inland, leaving a swath of destruction 150 miles wide. Beyond reckoning the losses, finding out precisely what happened has become a preoccupation for those seeking to salvage evidence of the shattered past.

The surge of Katrina was not, as might be imagined, simply a giant tidal wave that struck the beach, then carried the resulting wreckage out to sea. Instead it mounted steadily, bounding higher until it overtook the sea wall that lines much of the beach, advancing further with each crashing wave to slosh across streets and highways before roaring in a whitewater torrent over embankments, into buildings, back out, and in again. The tide reached the third floor of some structures, crowned by breaking, wind-driven waves, the force of which grew exponentially when coupled with the increasing weight of the water. Foundations were undermined, walls yielded to the stress, and rafts of wreckage, vehicles, and boats collected and acted as battering rams. Once the eye passed, the water began to fall and the flow reversed, but not uniformly, because the winds had shifted and the obstacles had moved. Debris was scattered everywhere.

Not surprisingly, locating art was not a high priority for most people in the immediate aftermath of the storm. Faced with recovering bodies and finding food, water, and shelter, “People were overwhelmed,” says Gwen Impson, who heads the Hancock County artists’ association known as “The Arts.” “People were dealing with life and death issues. But slowly it began to sink in, and people began to go through the piles of debris.”

There is still no official estimate of the total value of the artwork that was lost, and there may never be. Because so many collections were uninsured, often the only documentation was contained in the personal records of their owners, and sometimes those records, too, have vanished. Some of the artwork was never photographed. Jim Lamantia, a retired architect who is now an art collector, dealer, and part-time appraiser, says he lost the majority of his own collection, though his gallery in New Orleans was spared. “Monetarily, my loss was significant,” he says. None of his art, including his inventory in the gallery, was insured. “I can’t afford the sort of insurance I’d have to have,” he says.

Lamantia, who lives in Pass Christian and New York City, says he retrieved some of his paintings from debris piles, shipped a few to New York for restoration, and is creating collages from the remnants of his 18th century Piranesi paper prints. He says he is skeptical of some of the losses claimed by other collectors, but is not surprised that people would evacuate without their art. “The extent of Katrina was unimaginable,” he says. “We boarded up and comfortably left.” In some cases the only evidence of the value of the lost art is in surviving examples. Prior to the storm, Lord says he donated one painting from his collection, a watercolor of a Central Park scene by Maurice Pendergrass that appraised at $980,000, to the New Orleans Museum of Art. The museum’s director, John Bullard, confirms the donation.

“It’s a beautiful piece,” Bullard says, adding that although the museum did not participate in the appraisal, “$900,000 is certainly not out of line for a major Pendergrass painting.” (The museum’s collection survived.)

Blake Vonder Haar, whose New Orleans art restoration studio has traditionally drawn clients from the Gulf Coast, says her business has been deluged with artwork that was soaked with saltwater, caked with mud, ripped, faded, or disintegrating. “We’ve taken 4,000 pieces of damaged art since Katrina, but very few are from the Gulf Coast — I can count them on one hand — because most of them are just gone,” she says. Among the rare survivors, which she is currently restoring, is the oversized “Portrait of Jan de Groot” by artist Jerry Farnsworth, whose work also hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum in New York. The painting, which features de Groot with an owl on his shoulder, was pulled from a debris pile blocking a Biloxi street.

The incentive such finds gives to the continuing search is undercut by the preponderance of debris, the bewildering array of places to look, and the lack of an official clearinghouse for lost art, which makes it difficult to reunite found pieces with their owners. Most of the happy endings have come about by happenstance, and through word-of- mouth. As the storm retreats into history, the chances of finding more are rapidly dimming, yet many are reluctant to give up the search.

In addition to the portrait, the McMullans lost 700 volumes of books, photos taken during the Depression by author Eudora Welty, a set of original Audubon prints, and a letter from author William Faulkner describing his visit to the home. “I picture those bookcases falling over, and then the floors going, and all that water rushing under the house, and the books just fell into the hole and were carried away,” McMullan says. “That’s the only way I can visualize it.” Not long ago, she adds, “A woman called me and said she thought she’d found my portrait. It had washed up on the edge of the bay, in Bay St. Louis. But she described it to me and the color of the hair was different — it was black and my mother’s was reddish-blonde. The tilt of the head was different. I didn’t even get the woman’s name. It gets to the point that this whole thing is so painful you want to erase it. But you can’t.”

On a balmy, late spring day the narrow streets of old-town Bay St. Louis are bustling with the trucks of carpenters, plumbers, electricians, roofers, and painters. Like every other city on the Gulf Coast, Bay St. Louis, some 50 miles east of New Orleans, is recovering incrementally from the hurricane. Progress is measured by the degree to which signs of destruction are removed, like so many negatives reaching toward a positive conclusion. A church steeple still blocks the sidewalk on Main Street, but it has been repositioned, upright. A field of debris that once stretched to the horizon along the beach is slowly being whittled down. The National Guard staging area is gone, as are most of the relief workers. In the hollowed-out downtown, the clatter of nail guns mingles with the drone of a road grader on the scoured beach, where the driftwood is interspersed with antique windows, bits of architectural molding, a computer hard drive, toys. Shimmering like a mirage on the placid bay, a barge-mounted pile driver floats beside the topless piers of the old U.S.-90 bridge, which was washed out by the storm.

In what was once the South Beach historic district, amid the muddy, overturned cars and the mountains of architectural and household debris, Charles Gray’s immaculate silver Rolls Royce sits parked beside his tiny FEMA travel trailer. Gray’s domain is basically a clean slab, with large ferns in urns positioned at the front corners, carved from the ruined streetscape. Gray’s home, in a former warehouse that was undergoing restoration, was leveled by the storm, as were most of its neighbors. The back wall was the first to collapse, and fell inward, he says; the other three walls collapsed outward after the interior filled. Gray knows this because a family across the street — a man, woman, and two children — saw it happen as they struggled to save themselves. The family, he says, “was floating, trying to get to my roof, and when they got to within two or three hundred feet of it, my building collapsed, too.” The mother drowned, a fact that gives sobering context to Gray’s own material loss. “I’m 72, and I would only have used those things for ten more years or so, anyway,” he says, sounding only partly convinced.

Most significant among Gray’s losses, he says, were two Picassos and a painting reputedly done by Leonardo da Vinci, called “Boy with a Violin.” Also washed from the house was a self-portrait etching attributed to Rembrandt that, remarkably, Gray managed to recover from a debris pile a block away, a month after the storm. The etching is now at an art conservator, he says. Gray’s collection was also uninsured, and his explanation for the lack of coverage is that his provider refused him on the grounds that his building was only partially complete. The point is now largely moot because few insurance companies have honored hurricane policies, claiming the losses were the result of a flood, and many of the buildings lacked flood insurance because they were elevated atop comparatively high ground, outside the designated flood zones.

The contents of Gray’s collection were known to many in the local arts community, but the lack of insurance makes it impossible to verify his or many other losses, or to affix values. “Only one of the Picassos had been certified — a line drawing of a male nude with a strange little Queen Victoria-looking woman gawking at him,” he says. The reputed da Vinci, by his account, was once the subject of a controversy after an art critic suggested that it might actually be attributed to Rafael. After that, Gray says, it was removed from the Royal Academy of Art in London, and he bought it at an auction in the 1950s; in fact, there are very few known paintings attributed to da Vinci — Gray might just as easily say that he had a second rendition of “The Last Supper,” but that it is now sadly gone.

Gray has not come up entirely empty handed, as many have. In addition to the Rembrandt, he has found parts of his two crystal chandeliers, more than 1,000 of his 3,000 miniature figurines, several damaged museum-quality lacquered boxes from the former Soviet Union, “and a complete eight-piece setting of Chateau Chantilly china, which I found as recently as the day before yesterday, while I was digging in two or three inches of mud in my back yard.”

He says he hunted every day for three months. “My 1921 Chickering parlor grand piano, which is irreplaceable, I found a block away, upside down,” he says. “I’ve gone and sat on the carcass of that piano and cried a hundred times. It gets to the point where I was actually happier not to find the carcasses of things. Otherwise you can still hope they’re alive. It’s like that line from Tennessee Williams: ‘Ruined finery is all I have.’”

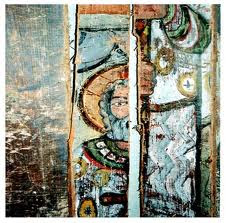

In addition to private collectors, many local artists were hard hit, in some cases losing their life’s work, their supplies, their studios, and their homes. Lori Gordon, a painter and mixed-media artist, lost her Clermont Harbor home and studio along with more than 800 pieces of her own art spanning a 40-year career, including her portrait of her late father. Most of her last year’s work survived in galleries that either did not flood or flooded to depths below the level at which her pieces were hanging. By far the biggest surprise, she says, was finding an intact stained glass window that had been given to her by an artist friend, which had been mounted in the front door of her house. Though the structure and the door were nowhere to be found, she found the stained glass on the ground, unbroken. Thus began the next phase of Gordon’s career — incorporating detritus from the storm into her mixed-media art. Gordon’s designs now include “pieces of the storm,” as she describes them — lost figurines, antique plates, stamped tin, clocks, dolls, carved angels, masks, Mardi Gras beads, watermarked sheet music and anything else that catches her eye amid the ruins. Searching the debris, she says, “fulfilled an emotional need. That broken plate takes on a significance way out of proportion.” During her first month of searching she found four of her paintings, damaged but still whole, as well as a few pencil drawings. “The vast majority of what I found were bits and pieces of paintings and bits and pieces of furniture, and as time went on and I was finding less and less of our own things, I started talking to friends and neighbors who invited me to go through their lots and see what I could find. Yesterday I found two more pieces of a friend’s African art collection. I know she’ll want those back.” Only once has someone recognized a personal possession in Gordon’s nascent, post-Katrina mixed-media work. In that case, “I had incorporated a fragment of a broken chair back, and she walked in, looked at it, pointed at it and said, ‘That’s it, that’s it — I need that piece of my chair!’ She needed it for a pattern to replace what she had lost, so I took it apart and gave it to her.”

Another artist, Bay St. Louis potter and painter Ruth Thompson, recalls roaming the wreckage of her neighborhood after the storm “feeling like I was in the middle of a Salvador Dali painting — it was surreal. And I noticed that after the storm, when I started painting again, my style had changed dramatically.” To illustrate, she pulls out examples of her work, pre- and post-Katrina. Before, her style was impressionistic: A typical scene was a serene garden reminiscent of a Monet. Since the storm, she has painted bold, abstract studies, often of demons and birds with gaping mouths.

Hundreds of other artists have experienced similar losses. The Gulf Coast Art Association, founded in 1926, with 80 active artists, was hosting an exhibit in the Gulfport library when Katrina hit, and none of the art has been found, says member Shirley Sweeney. Another member had paintings hanging in the visitor’s center of the Gulf Islands National Seashore in Ocean Springs, all of which were lost. The Singing River Art Association, based in Pascagoula, also had works hanging in the Gulf Islands visitor’s center, a few of which were later found on the beach, and in Biloxi’s J. L. Scott Marine Center, all of which were lost. Some artwork belonging to another Singing River member was returned after being uncovered in the debris along four blocks of Pascagoula’s Market Street. The consensus is that much of the lost art certainly washed out to sea, but, says Impson, “We’ll never know how much washed out. There are people still unaccounted for. There’ll be mysteries, always, after the hurricane.”

Yet because the surge was so powerful, an unusually large amount of debris was snagged by obstacles further inland, and so, observes Mary Anderson Pickard, daughter of renowned Ocean Springs artist Walter Anderson, “Every time you try to make a generalization about where things were going, it gets contradicted.” Almost all of her father’s work, which was the subject of an exhibit at the Smithsonian in 2003, was lost or damaged by the storm. Still, volunteer searchers recently found several paintings done by Pickard’s uncle, Mac Anderson, across the Ocean Springs harbor, a mile northwest of the Shearwater Pottery compound where the family of artists lived and worked before the storm. Other items, meanwhile, have been found in opposite directions. “We found a good many things buried in muddy sand, and I think we’ll probably continue to find things,” Pickard says. “Last week we had chicken bones turning up on the Gulfport beach again, from the trucks that were parked at the pier when the storm hit, going to Russia or somewhere. Things are washing in. When we have a storm, or a very high tide, more things will wash back in.”

In addition to art that was never seen amid the piles of debris, some works were actually discarded as waste in the bewilderment and confusion after the storm, Bergin says. In Gulfport’s Whitney Bank building, where his office was located, the lobby contained several pieces of high-quality abstract art, and most of what did not wash out on the surge was later hauled away, he says. “I dream about those pieces, being able to find them in the area where they take all the debris, being able to pull them out and do something with them. I imagine the debris sites are just inundated with so many works buried.”

Among those who searched the debris for art, photographs, or anything of value to its former owners was Gulfport attorney and art collector Tom Teel. “All that’s left of my office is some old tabby steps,” he says, referring to the mixture of ground oyster shells and cement that was once a common building material on the coast. “And we’d find all these pictures, all gnarled and wet, and we didn’t know who they belonged to, so we’d stick them there on the steps, and every few days I’d go by and some of them would be gone, as people found them, so we’d add a few more.” Teel, who lost an eclectic collection of art ranging from 19th century oil paintings to an original photograph of Martin Luther King Jr., expects other pieces to turn up over time, though not necessarily in salvageable condition. “Tons of things will be found by shrimpers,” he says. “Already I know one shrimper found some World War I relics, including a bugle that had washed out and came up in his net.”

The closest disposal site to Pass Christian is the Firetower Landfill, just north of I-10, which was among 50 or so emergency burn pits, disposal sites and transfer stations set up after the storm. “We have seen some art come in,” says Herman Kitchens, who works for Advanced Disposal, the operator of the landfill. “But none of it’s worth salvaging. It’s mostly wet stuff and broken frames. After all the machinery handling, it’s torn to bits. I haven’t seen anything you’d want to keep — it’s mostly things without much value, like you’d see (hanging) in a nursing home.” In the months immediately after the storm, Kitchens says, “You did see a lot of people going through the debris piles. And I know a guy who hauls in here who was a shrimper, and he said he brought up some artifacts in his net that came from Beauvoir (Jefferson Davis’s last home, in Biloxi). But we go flounder-gigging just about every night, and about all we’ve seen is all the Wal-Mart stuff that’s washed up against the jetty.”

On this particular day a steady stream of dump trucks comes and goes along the rutted gravel road to the former dirt mine, which has been transformed into a mass of pulverized debris perhaps 50 feet high and several hundred yards long. At one end is the so-called “vegetative debris” — mostly trees and brush. Beside that sprawls a mound of tires, beyond which is the sorting area, where other types of refuse, including construction and demolition materials, are shunted to the main landfill, where any art would have likely ended up. It is hard to imagine finding anything recoverable in the waste, which was battered by wind and waves and steeped in salty, bacteria- and mold-laden piles before being bulldozed, loaded into trucks, dumped at the landfill, then compacted and covered with compost. Still, people look.

During the height of the cleanup, as many as 240 dump trucks per day unloaded at the Firetower site, which now contains about 700,000 cubic yards of debris. (By comparison, about ten million cubic yards were removed from the World Trade Center site). “Everyone just wants to get the stuff out of the way as quickly as possible,” says Billy Warden, who heads the solid waste permitting division of the state Department of Environmental Quality, adding that during the collecting and sorting of debris, “We had spotters looking for (chemical) drums, electronics, tires. It was all a jumbled mess, as you can imagine. The tidal surge just rolled all this stuff together. It was everything that would be in your house — clothes, cell phones, photo albums. I never heard of anyone finding any art.”

Even among those in a position to recognize art at the debris sites, knowledge is typically rudimentary and of only passing interest. When asked about the prospects for finding lost artwork, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers employee suggests talking with “someone at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum” — an apparent reference to the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum, under construction in Ocean Springs to house the pottery of local master George Ohr, otherwise known as “the Mad Potter of Biloxi.” Ohr-O’Keefe Museum director Marjie Gowdy laughs when she hears of the mistake. “It happens all the time,” she says. Yet the museum, an affiliate of the Smithsonian, had already begun to make a name for itself before its Frank Gehry-designed facility was finished. The museum now has the bittersweet distinction of owning the most valuable collection of art on the Gulf Coast that remains intact. The campus itself is another story; gone is the Pleasant Reed House, built by a freed slave, which was being converted to an African American museum, as well as antebellum Tullis-Toledano Manor, considered by many to have been the best example of Gulf Coast vernacular architecture, which was flattened by an unmoored casino barge. Also damaged was the African American Art wing of the museum, though the graceful live oaks around which Gehry designed the complex survived. Ohr is widely regarded as a pottery genius, known for his pinched, folded, and twisted clay designs that were both eccentric and refined. A single piece has sold for as much as $84,000. His unconventional style reportedly attracted Gehry — most famous for the Guggenheim art museum in Bilbao, Spain, to design the project. Ohr’s pottery came through the storm unscathed on the second floor of the Biloxi library, but “deteriorating security,” as Gowdy puts it, prompted its relocation to the Mobile Museum of Art a week later, where it stayed for one year. It is now in an undisclosed vault north of the Gulf Coast.

Deteriorating security — otherwise known as looting – may have been a factor in the loss of artwork elsewhere, observes Lord, who evacuated with 60 pieces from his own collection but says that of the 200 he left behind, 17 survived on the second floor and were believed to have been stolen later, including works by Jose Orozco, George Luks, and Mark Rothko. “Those 17 were assessed at $2.6 million,” he says. While he did have insurance, Lord says it was not nearly enough to cover his loss. He leafs through a long list of the missing pieces, which include 19th century American landscapes by artists Ralph Blakelock, George Bickerstaff, and Edward Willard Deming as well as modern art by Joseph Meert, Max Weber, and Man Ray. Others say that in the rarefied atmosphere of the cleanup, finders of lost art no doubt occasionally turned into keepers, whether by design or by default.

In the weeks after the hurricane, the entire Gulf Coast was cordoned off and permits were required of anyone seeking to travel to the beachfront. Nowhere was visitor scrutiny more rigorous than in Pass Christian, which was a wealthy enclave of waterfront mansions that claimed the oldest yacht club in the South. Though devastated by the storm, Pass Christian retains more of its lavish residences than any other city on the coast, and those that survived were blown open by the storm, often with valuable furnishings and still hanging artwork visible through gaping holes in the facades. The Pass Christian beachfront is now a scene of architectural triage, with several of the surviving mansions undergoing restoration or being painstakingly returned to their foundations by house movers, and others being demolished or rebuilt from the ground up. At the McMullans’ house, blown-out windows and doors and a large hole in the front wall are now patched with plywood, awaiting a construction crew.

McMullan says that she initially hesitated about repairing the house, but decided to proceed after realizing it was now the oldest structure in town, after the previous titleholder was destroyed by the surge. Today, the lawn is mostly clear of debris, the live oaks are sprouting new growth, and the jasmine is blooming. The sounds of nail guns reverberate from the gutted house next door, while in the other direction, a backhoe groans. McMullan’s initial uncertainty stemmed in part from the pain of loss, she says. “Some of those things — the Audubon prints, the Welty photos, you can still get them. But it’s just too painful to think of hanging anything on those walls right now.” Others express fear that the empty spaces of the Gulf Coast will be filled by garish casinos, condos, and commercial strips. There is also the question of why anyone would invest so much — including priceless collections of art — in what has proved to be an untenable hurricane zone. As if acknowledging the obvious, the logo of the Corps of Engineers’ recovery program features the agency’s symbol — a castle, but in this case built of sand.

Lori Gordon laughs when asked why so much valuable art was placed in harm’s way, and why so many people are rushing to do it again. “It has to do with this little thing called home,” she says. “No matter what’s staring you in the face, when you get emotionally attached to a place, when you get emotionally attached to things, it defies logic. The people who aren’t emotionally attached — they’re already gone.” Gordon says she has no choice but to move inland herself, in one part due to the wildly escalating cost of hurricane insurance (in some cases, by as much as 400 percent) and the planned construction of high-rise condos in her neighborhood. “That hurts more than the storm,” she says. “Katrina took my house, but circumstances are now robbing me of my home.”

McMullan’s daughter, Margaret, says she always felt trepidation about leaving valuable possessions in the family’s beachfront home, even though the house had survived innumerable hurricanes during its 160 years. “I was always the one closing up before a hurricane, and I’d be thinking, what are we going to do if all this stuff goes? I had a friend visiting once from Los Angeles, and we were walking through the library, where the Eudora Welty photos were, and she said, ‘Why are you keeping these in here? It’s the worst place, with the salt air.’ And my father said, ‘So what? This is where I want to enjoy them.’ My parents, they just want to be amongst that stuff.” She agrees with her mother’s assessment of the monetary value of her grandmother’s portrait. “It’s not a great painting. It’s overly pretty — she looked like one of those Gibson Girls. I always thought the artist should have given her more substance, but the funny thing is, even though my mother got it framed and restored in New Orleans, you could still see those crease marks where it was folded, and that was what I really liked about it. To me, that was its substance.” The same could now be said of the watermarks and muddy stains on much of the art recovered after Katrina, though Pickard, for one, says the scars are too fresh to see it that way now.

Notably, many of the surviving collections, both public and private, are expected to return to their beachfront venues once the necessary restorations are complete. Before Katrina, Vonder Haar’s studio had restored 168 pieces of artwork from Beauvoir, Jefferson Davis’s home, which was built in 1852 and elevated about eight feet above the ground on Biloxi’s beachfront boulevard. The last of the artwork was returned to the house two months before Katrina, and much of it was subsequently soaked or ripped by debris, including portraits of Davis and of his daughter, the latter of which Vonder Haar says took 200 hours to restore the first time around. The three most valuable of the damaged paintings are being restored, again, at Delaware’s Winterthur Museum, and will eventually be returned to the house.

The Ohr-O’Keefe Museum, which had been scheduled to open in June, is now expected to open in 2008 at the same location. All the necessary protective measures — including reinforcing the walls of the lower level — will be put into place to ensure that the collection is safe, and FEMA has ruled that the building does not have to be further elevated, Gowdy says. “I’ve thought about it a lot, and it does seem risky,” Gowdy says of the extensive collections of art and artists’ studios on the Gulf Coast. “But when it’s beautiful here, it’s so beautiful, and you want to be by the water. People just get enchanted by the Gulf Coast lifestyle. That’s why the artists are going to come back.” She says the art community has also been bolstered by emergency funding from groups such as the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Ford Foundation, and government agencies including the Mississippi Arts Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Bergin predicts that collecting will resume in earnest once some semblance of normalcy returns. “It’s like I told my wife when we were sifting through the debris: You work all your life to collect, you go to the auctions, you make day trips to galleries in New Orleans and meet artists, you preserve and restore, yet in one fell swoop all that effort is washed away.” Yet soon after the storm, Bergin says he began decorating the RV his family moved into with reclaimed artworks, including paintings by Alexander Calder and Peter Max. “It’s our fix to surround ourselves with what we’ve salvaged,” he says. “It’s an addiction. After the storm, rather than go for food and the file cabinets, what the hell do I do? I go for the artwork. It’s total nonsense. We were without food for nearly three days because of that. We should have been saving food.” The days of searching are now something of a blur, he says. “In the beginning we were all feeling hurt and shocked, and I threw out some things, and I wish I had it to do over again. It was so hurtful to see things that were no longer what they used to be. I wanted to be removed from reality, did not want to salvage or save. The pieces seemed somehow less valuable, and at first you don’t want anything that will remind you of this horrific event. But the further along we go, it’s like a death, where years later you can deal with it. And I realize that what’s left — it’s all even more valuable now.”

In the old days, before August 29, 2005, the Anderson family’s Shearwater complex in Ocean Springs was an enclave of weathered wooden buildings set amid towering oaks, magnolias, and pines, overlooking the water. Several of the Andersons were or are painters, sculptors, or potters, and many lived and worked in the 28-acre compound, which was anchored by a house built in the 1830s. The most famous among them was Walter Anderson, who produced vivid paintings, murals, and journals recording natural scenes along the Gulf Coast. For many, the damage and destruction of his work represents the most tragic loss of art as a result of Katrina.

Pickard, Anderson’s daughter, stands before the surviving potters’ sheds, which were wrecked by the surge but are being meticulously, lovingly, and somewhat feverishly reconstructed by her son Jason Stebly, using boards and beams retrieved from collapsed buildings or from the nearby marsh, and new lumber milled from old-growth pines felled by the hurricane. “He won’t quit,” Pickard says of her son. “It’s his raison d’etre. He quit his job to do this.”

Pickard, whose soft, open smile occasionally fades as she fights back tears, normally exudes a palpable sense of purpose that now seems on the verge of wavering. She says of her son’s heroic efforts, “I think: Why is he doing this, giving up his whole life, trying to rebuild something that’s gone?”

Stebly is a tall, strong, concentrated man. His skin already brown from the late-spring sun, he is soaked with sweat down to his khaki shorts and running shoes. “Aren’t these boards beautiful?” he asks, gesturing toward the wide planks in the floor of the main potters’ building, which he rescued from a wrecked building nearby. His carpentry is solid, and is a work of art itself. Stepping outside for a smoke, he picks up a few pottery shards and says, “Here’s what I found today.” The pottery was illustrated by his grandfather, he says. Then his eyes roam up the artfully twisted trunk of a tree that appears to embrace the trunk of another beside it, smiles, says, “Black gum,” as if entering a note in a log.

There has been a great deal of cataloging at Shearwater during the last nine months, both on paper and in the minds of the Anderson family. “There were treasures in every building,” Pickard says as she strolls past the empty foundations. “The buildings themselves were art. They were sacred spaces. I lie awake at night trying to reconstruct how it happened, how it was all here and then it was gone. I don’t want to know, but I’m driven to know. What happens is, if you find something like a doll my father made for me from a cypress knee, it’s magnified and made more precious and sanctified. I’ve never been a ‘thing’ person who attaches to dishes or silver, but I had so many treasures that I will never get back again. And I’m coming to realize that those things are an illusion.”

Among the structural casualties were most of the Anderson family homes as well as the Shearwater Pottery showroom, which contained works by family members and others who visited during the decades since the artists’ colony was founded in 1928. The losses also include collections of museum-quality ceramics and pottery as well as a portrait of Pickard’s great grandmother by painter Cecelia Beau. Walter Anderson’s studio cottage survived the storm, though it was washed from its foundation, and has since been moved back. Anderson’s most famous murals, which once adorned the interior of the cottage, had been moved to the local museum that bears his name years ago, and survived.

Perhaps most traumatic, not only for the Andersons but also for the art world, was the flooding of the vault in which the majority of Walter Anderson’s watercolors were archived. Though designed to be wind- and waterproof and elevated three feet above the height of the surge of Hurricane Camille, in 1969 (the benchmark storm prior to Katrina), the vault was breached by debris that smashed the double-sealed steel doors. Today it has the feel of a dank, pilfered mausoleum, and the dented doors look as if they were burst open by a SWAT team. Many of the paintings bled onto their separating papers, which created shadows of their images on the blank page — art that was essentially created by the storm, at the expense of the originals.

The primary motivation behind Anderson’s art, based on his journals, was his desire to understand and exalt nature — to “realize” it, in his words, and toward that aim he frequently rowed alone to Horn Island, a low-lying barrier island a dozen or so miles offshore, to paint for weeks at a time. He saw art everywhere there, and sculpted “The Swimmer,” one of the featured pieces at the Smithsonian exhibit, from a tree felled by the 1947 hurricane. In 1965, the year he died, Anderson rowed to Horn Island to experience Hurricane Betsy, alone and unprotected.

“My father always saw his art as ephemeral, though he had his box of favorites,” Pickard says as she stands beneath wind-stripped trees that now sport clumps of verdant, exaggerated re-growth. “He had an intense admiration for the power of storms. He was awed by them and wanted to be in them. He saw them as a catalyst for change. I’m trying hard to get to that place, to see that it’s going to push us all into being different people. I’m sure he would have known about global warming, and my own feeling is that this has been an indication that this part of the coast is no longer to be occupied. I don’t think we’re meant to stay on it now. Each time I go out I feel like I’m going out on land that’s already been taken. The earth is trying to cool itself. Yet it’s human nature: We scurry back.”

Over the years, some of Anderson’s paintings have been sold — usually examples of subjects of which there were many iterations, but for the most part his life work had remained in one place. The family created block prints of some of his works to make them available to the general public, and more than 300 silk screens were recovered and are temporarily stored in a tent at the center of the compound. But Pickard’s brother John Anderson, who acts as the curator of the family’s collection, estimates that more than 80 percent of his father’s work was damaged, and 300 of his best paintings were destroyed. “We’re talking about paintings that have been published in books — icons of his work,”

he says. Some were buried in the muck at the bottom of the vault, while others floated away. Many of those that survived are now housed at Mississippi State University, awaiting restoration, which Anderson says “will take years and cost millions of dollars” — money that the family does not have, because the collection was not insured. “In the past, people have told us we should take Daddy’s art to New York, that we could get rich, but that was not the objective,” Anderson says. “We kept the art here to keep it in close proximity to the Walter Anderson Museum of Art, and people came to us, which is part of the miracle.” He says he has given a lot of thought to how his father would have reacted to the loss. “He’d probably say we’re focusing on preserving too much,” he says, and offers as evidence an episode that took place at Oldfields Plantation, which belonged to his mother’s family, and where his parents lived for a time. At some point, he says, his mother’s father “needed some money, so he cut a large section of old growth timber, this very beautiful forest, and Daddy cried. Then the next year it received sunlight where it hadn’t been before, and flowers sprang up in incredible profusion, and he painted a mural of that rebirth called ‘The Cutover.’ It was about the endless circle of destruction and creation, about the resurrection. But what Daddy did — he wasn’t really just painting birds and fish, he was painting a moment in time, a quintessential moment in time, and if one of them is lost, it can’t ever be recovered.”

In the days after the storm, the family searched feverishly for lost art, Pickard says. “We recovered at least three paintings, and lots of people tried, but it was very hot and dangerous. We hunted very intently for two months and after that I got sick of it; then after it got cool I did it again. I think there are probably still things there to be found, but a lot of what I found was just empty frames.” Among the found works was a mural called “The Saints,” which Walter Anderson painted on boards, and which originally hung in his first studio, built by the water in 1930. “On the wall of his studio he painted Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, as well as St. George and the dragon and the princess,” Pickard says. Though the studio was destroyed by Hurricane Camille, its foundation was incorporated into a patio of Pickard’s home, also now gone. After Camille, she says, “We found the boards all over the Shearwater acres and across the harbor. When I built my house, they were mine, so I put them back as close as I could to the place where they’d been, where the studio had been. When Katrina came, again the boards were taken and again we found them, all but one. About three were in the same place in that marsh behind where the showroom used to be. My feeling is they were meant to stay on the property. Jason made it one of his priorities when he was going through the debris to find those boards, and one day he was really tired and he closed his eyes and said please let me find one, and he felt someone looking at him and he turned around and saw half of a saint’s face.” The mural, short one board, now leans against a wall at the home of another of Anderson’s daughters, Leif. Though the boards are weathered, the gilded faces of the saints shimmer like stylized images from a pre-Raphaelite painting.

Pickard is visibly proud of her father’s mural, but the look in her eyes reflects her assessment that things of value are an illusion, that they cannot be depended upon. She is chastened by the cumulative losses, and is as dubious about the future as her son is driven to rebuild the past. Back at the potters’ sheds, she finds Stebly hard at work, as always. The sheds are becoming works of quiet, functional beauty, as he prepares them for the creativity of others. Stebly works all day, every day, Pickard says, then falls asleep, exhausted, in a bed set beneath a tarp by the water. “Why is he doing it?” she asks. “I just keep thinking: It’s all going to be gone.”

The question could be asked of many people across the Gulf Coast, and, for that matter, anywhere: Why does anyone create or preserve, knowing that nothing ultimately lasts? Over the phone, John Anderson mulls the question. Then, in a voice so soft that it is sometimes difficult to hear, he says, “The truth is, Jason seems to have found himself. He has found an identity after the storm. He’s found what matters to him.”