A Way Station for the Blues

From Howlin’ Wolf to Duke Ellington to Tina Turner, the best of the best rolled on through the Riverside Hotel.

By Alan Huffman http://www.meridian.net/mississippi/2016/11/23/13729310/mississippi-riverside-hotel

The Muddy Waters room at Clarksdale, Mississippi’s Riverside Hotel isn’t just a tribute to the famous blues artist who was born McKinley Morganfield on a nearby cotton plantation. It’s the actual room, with the same bed where Waters stayed when he was traveling the Delta blues circuit in the 1940s and ’50s.

The same goes for the Sonny Boy Williamson room, the Ike Turner room, the Sam Cooke room, the Robert Nighthawk room, and the two John Lee Hooker rooms — one upstairs and one down, because “he had two lady friends,” recalls Joyce Lyn Ratliff.

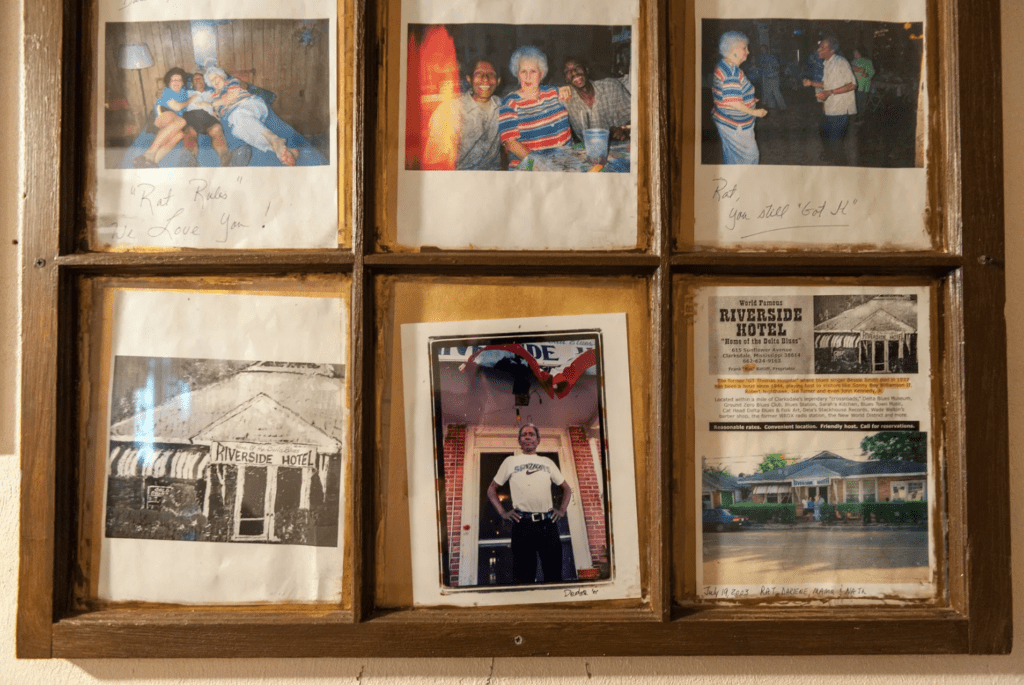

She, along with her daughter Zelena, are the latest Ratliffs to run the Riverside, having inherited it in 2013 from her late husband Frank (known to everyone as Rat), who in turn took over after the death of his mother, Z.L. Hill, who founded the hotel in 1944.

The hallway is filled with music mementos from the folks who passed through over the years.

The hallway is filled with music mementos from the folks who passed through over the years.

The musicians were regular guests and had their favorite rooms, says Zelena, who goes by Zee. Empress of the Blues Bessie Smith died in her room from injuries sustained in a car wreck on Highway 61, a time when the Riverside building was a hospital for African Americans. Other guests have included Howlin’ Wolf, Papa Staples, Duke Ellington and C.L. Franklin, a locally famous Baptist minister who was also Aretha’s dad.

Howlin’ Wolf was here.

Howlin’ Wolf was here.

Tina Turner napped on the couch in the office one afternoon after arriving exhausted from touring with her then-husband Ike, who was born in Clarksdale and stayed at the Riverside for extended periods in the early days of his career. After Ike and Tina became famous, he often stopped by when he was in the area, recalls Joyce Lyn, whom everyone calls Mama, adding that her mother-in-law couldn’t help noticing that “there was a lot of wigs in their car.”

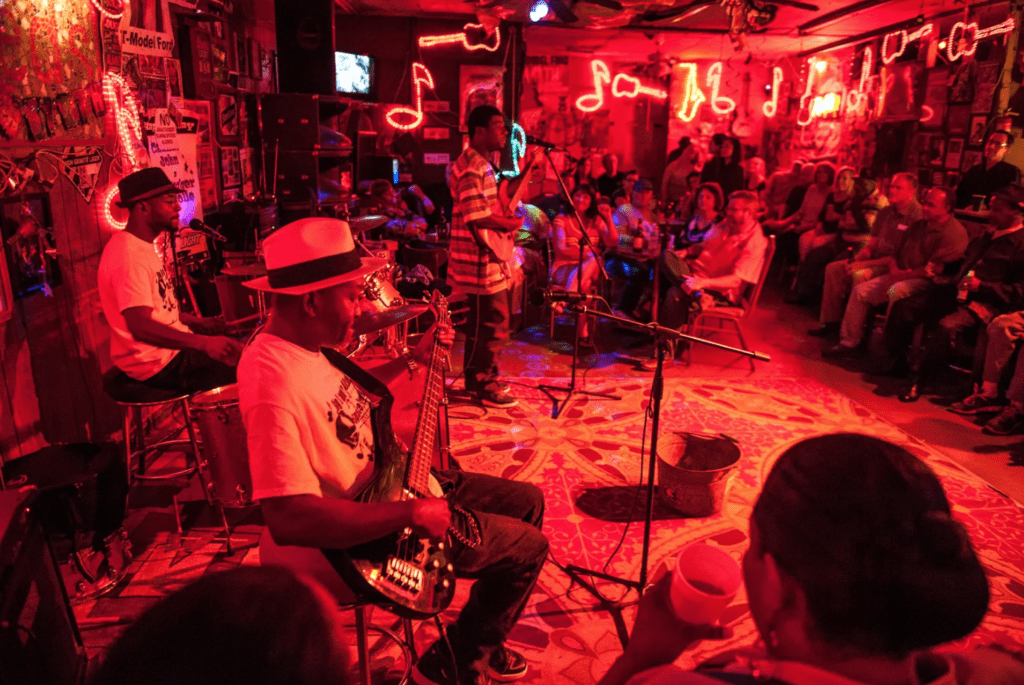

Such memories come flooding back as Mama and Zee sit by the curb in front of the Riverside on a recent autumn afternoon, as R&B emanates from a house across the way and rap rattles the speakers of passing cars. In a few hours, Anthony “Big A” Sherrod’s band will crank up at Red’s lounge, a blues venue a few blocks away that is as close to a typical juke joint as most visitors will ever get. The newer, painstakingly funky Ground Zero Blues Club owned by actor Morgan Freeman is also within walking distance.

Clarksdale was at the epicenter of the blues from the 1940s to the 1960s. The Riverside was a major gathering place, as were the local juke joints close by.

“John Lee Hooker used to play out here,” Mama says, gesturing to the sidewalk on either side of her. Musicians sometimes played in the hotel’s basement or under the shade trees on the banks of the listless, cypress-lined Sunflower River, which flows (more or less) behind the hotel.

Mama herself grew up “near the crossroads,” she says, evoking the site where bluesman Robert Johnson supposedly sold his soul to the devil — though which crossroads he was talking about is still debated. “They argue about it, child,” she says. “Where is the crossroads. Back then, Robert Johnson had his little thing goin’ on out in the country, at a little juke joint. But those places, they all gone now.”

From the vantage point of the Riverside, it’s easy to see why music is the focus of tourism in this Delta town, which hosts two annual blues festivals and is rife with blues trail historical markers. Music is everywhere and has been for the better part of a century, though it was mostly underground until the 1970s. In response to increasing numbers of blues travelers, Clarksdale’s promoters have ensured that music is playing somewhere every night, and lodgings have sprung up to handle the influx, including an array of B&Bs and Airbnbs. The popular Shack Up Inn is a conglomeration of refurbished tenant shacks and new renditions that seek to replicate the blues experience, only with air conditioning and indoor plumbing.

But among the blues sites, none compares in authenticity with the Riverside, which Zee manages, as her father and grandmother did, as a way station for serious blues travelers. As she and her mother talk, a Canadian woman they introduce as Ms. Laura saunters up, carrying a go-cup of beer. After spending the afternoon listening to blues at a place called Hambone, Ms. Laura is slightly tipsy. She says that she’s on a solo blues pilgrimage and is sleeping in the Muddy Waters room. “I can’t believe how lucky I was to find this place,” she says. She heard about it from two sources: a blues travel book and a guy in a bar in Chicago.

“We get people from all over,” Zee says. “Now I see and understand why my dad and my grandmother felt so special about it. I don’t go nowhere, but the world comes to me.” The guest register includes visitors from Sweden, the Netherlands, and Italy, among other countries. The first blues tourists to arrive were from Japan in the 1970s, during a period when the Riverside relied mostly on boarders because their blues musician regulars had gotten too famous or too old to perform in the local joints, Mama says. By then, Zee adds, the musicians who frequented the Riverside were mostly soul and R&B singers. Today, the blues musicians who visit tend to be white. They come for inspiration.

As Zee talks, a young couple arrives to check the place out, but declines to book a room due to the lack of televisions. “You know I ain’t got no TV,” Zee says after they drive away.

The hotel’s 16 rooms are, in fact, spartan period sets with shared bathrooms down a long, tilting hallway. Three small, decrepit houses next door catch the overflow. This is a hotel for which guests must be game. “When people come here now, they come for the experience,” Zee says. “Nothing much has changed except what my dad did with his own hands.”

There’s no piped-in blues music, though there is Wifi, because international travelers need it to communicate with friends and families back home, Zee says. The hotel’s office tends to have a “Closed” sign in the window, even when it’s open, and is crowded with memorabilia, including a shrine to Rat featuring paintings and photos of him, a Silvertone guitar that a guest donated for others to play, and the suitcase that Robert Nighthawk left behind and never retrieved (he died in 1967).

The ghosts of Rat and his mother exert a powerful presence in the stories that Zee, her mother, and others around town like to tell. “My grandmother knew her boys was struggling because they were musicians,” Zee says. “She cooked for them, she sent them to LaVene’s Music Store so they could buy instruments to play, and pay their board. They felt safe here.” Though the LeVene’s building is now occupied by Red’s lounge, newer music stores have sprung up to fill the niche, and along the city’s otherwise vacant streets are a scattering of blues venues, dive bars, cafes, and restaurants.

Owner of Pete’s Grill, Adrian Allen, poses for a portrait.

Owner of Pete’s Grill, Adrian Allen, poses for a portrait.

Clarksdale’s heyday has clearly passed — the downtown is notable for block after block of lovely, empty storefronts, but it has found a kind of rebirth in the blues. Across from Ground Zero is the impressive Delta Blues Museum, which includes among its displays the relocated log cabin that was the childhood home of Muddy Waters, who popularized the phrase “rolling stone” in his eponymous 1950 song. Like so much about the blues, that’s but one thing that was later co-opted by others, including a certain magazine and a British rock group.

Tourism in the Mississippi Delta today almost invariably revolves around the blues, with juke joints that once attracted mostly local African Americans and the occasional international blues fan now serving as mainstream draws, which has helped both to preserve and to gentrify the genre. As Adrian Allen, owner of Pete’s, the nearest bar to the hotel, observes, “The Riverside is real. But 97 percent, maybe 99 percent of their guests are white.” Allen says that when Rat was alive, “He’d walk guests over here to introduce them and let them know it’s okay.” In many ways, Pete’s — an unassuming place known for what Zee describes as “the meanest wings in town” — is more like a traditional joint than venues that cater to tourists, though it only hosts live music during the annual Juke Joint Festival.

Ellis Coleman poses for a portrait at Red’s Blues Club in Clarksdale.

Ellis Coleman poses for a portrait at Red’s Blues Club in Clarksdale.

A couple of blocks away, Big A’s band cranks up at Red’s soon after dark, eliciting markedly different responses from its integrated audience. A few patrons sit stiffly in chairs, as if observing a curated cultural presentation, while others — including blues artist Super Chikan’s brother, Ellis Coleman — tear up the dance floor. The place is packed, bathed in red lights.

Though blues tourism has clearly gone mainstream in Clarksdale, for Zee it’s still about the music and the stories that go with it. One of her favorites, she says, is about the time John F. Kennedy, Jr. stayed in one of the Riverside’s cabins during a trip to celebrate finally passing the bar exam in 1991. “My grandmama kept her mouth closed about John-John being here,” she says. “He stayed for three days, and every morning he ate his cereal on my grandmama’s bed and listened to her tell stories.” A framed newspaper clipping in the hall commemorates the visit, which was eventually leaked. The headline notes that People magazine’s “Sexiest Man Alive” had spent a weekend in Clarksdale visiting blues sites and the cotton harvest.

Zee says most of their guests still hear about the place by word of mouth. As a result, many travelers miss out. At one point during our stay, an Australian couple happened upon the hotel and said they wished they’d known about it before they checked into a chain motel out on the highway. “We’re headed to Memphis next,” the man said, “and we’re hoping we can find someplace like it there.”

To that there could be only one response: Don’t count on it. As anyone who’s stayed at the Riverside can attest, there’s no place remotely like it.

Photos by Rory Doyle.

Watch a short video about the Riverside Hotel here:

https://www.facebook.com/travel.meridian/videos/1122663934516664/?pnref=story